Today is the one year anniversary of the sad red earth. Before December 2, 2008 my general response to the idea of authoring a blog (from people, generally, who seemed, for some reason, to want me out of their ear for a reasonable period of time) was “I don’t want to write no blog thing.” Or something along those lines. Julia’s was “Oh, fun! Are you going to do the work?” Thus is infamy visited upon the world.

Gifts of appreciation (or bribes to retreat from the scene), in the form of fine chocolate and Super Tuscan wine may be sent to

1nth the sad red earth The Milky Way GalaxyThe Universe No Controlling Authority

To mark the day, and to catch latecomers up on how this questionable enterprise all began, we offer below the first two posts to appear on the sad red earth, both a year ago today, the first by Julia, the second written by me and photographed by Julia. Thanks to all our readers, viewers, and commenters of all stripes: the sad red earth is only our fevered affliction without you, and some form of syndrome it appears to be, for there is much more to come.

AJA & JD

How We Named Our Blog…

In 1993, I spent five months in India working on a children’s book and other photographic projects. I remember some pretty lonely moments. One of those times was during a nine-hour bus ride of heavy thoughts from Mangalore to Bangalore, alone in a third world country without another living soul aware of my whereabouts. This was years before internet and international cell phones.

This leg of my trip was unexpected. My film, sent from Nebraska to Mangalore, was sitting in the Customs office in Bangalore waiting for me to claim it. So instead of moving north up the coast in route to Bombay and my next magazine assignment, I boarded a pre-dawn bus, for an out-of-the-way ride eastward to the landlocked state capital.

I arrived early at the bus station and took great care in selecting my seat. At the last minute, a large Indian man sat next to me, his body overextending his seat into mine, touching my left side from shoulder to knee until he got off at his predetermined destination five hours later.

A young child with matted black hair thrust a beat up stainless steel plate at me with a few coins on it, gurgling sounds while she begged.

Our first stop was for breakfast. We all piled off the bus and into a restaurant where I sat silently with three men, feeling unsocial while I drank a cup of coffee and watched them eat with their hands. A shrill whistle sounded. It was time to get back on. I climbed over the fat man and stuck my head out the window. A young child with matted black hair thrust a beat up stainless steel plate at me with a few coins on it, gurgling sounds while she begged.

All day, I took everything in as our bus chugged up mountainous roads and passed other vehicles carelessly going down. My world was seen through a sequence of still images, captured in horizontal frames. It was a lonely day, a sad day. Everything around me seemed so depressing.

At our next 10 minute stop, I scurried off in search of a bathroom, though it was closed for some reason. Overuse? There was smelly water covering the floor. A small boy was defecating outside, in front of God and everyone else. Hundreds of people were standing around, women in their brightly colored saris and men in their drab white, brown, or black attire. Everyone was headed somewhere, or nowhere, under the colorless light of the mid-day sun.

The fat man got off the bus and an old woman with a thick mustache and stubble of a beard took the seat next to me. Her skin was the color and texture of a piece of beef jerky. She reached across me with a frown on her masculine face and closed my window. Our eyes met briefly, and I proceeded to stare out at the passing landscape, my nose pressed up against the glass, immersed in my thoughts.

The scenery changed drastically from that with which I had become familiar on the coast: lush green rice paddy fields and groves of coconut trees. For brief moments it was as if I were in the Nebraska Sandhills with its rolling land covered by dry sagebrush; or in Arizona, where the earth is red and cactus line the roads. But there were sure signs that I was not in America: a water buffalo submerged in a pond, harnessed oxen tilling a field guided by a weather-beaten barefoot farmer, women washing their clothes under a communal faucet, while a naked young boy bathed.

The “movie” outside my window seemed to be stuck on slow speed. It felt as if our bus was the only thing moving.

I was reading Jack Kerouc’s novel On the Road during this momentous bus ride and came to the following line: “I felt like a speck on the surface of the sad red earth.” It was exactly how I felt.

Then things got better.

We flew by what appeared to be a mirage in this otherwise dry, brown, lifeless environment, adding color to my dark mood: two small square pieces of irrigated land, one of bright green, the other a golden yellow. Between them, on a raised footpath, ran a woman wearing a sari that matched the yellow field, flowing behind her and aglow from the backlit sun.

Ah, there was life after all. My spirits were lifted.

JD

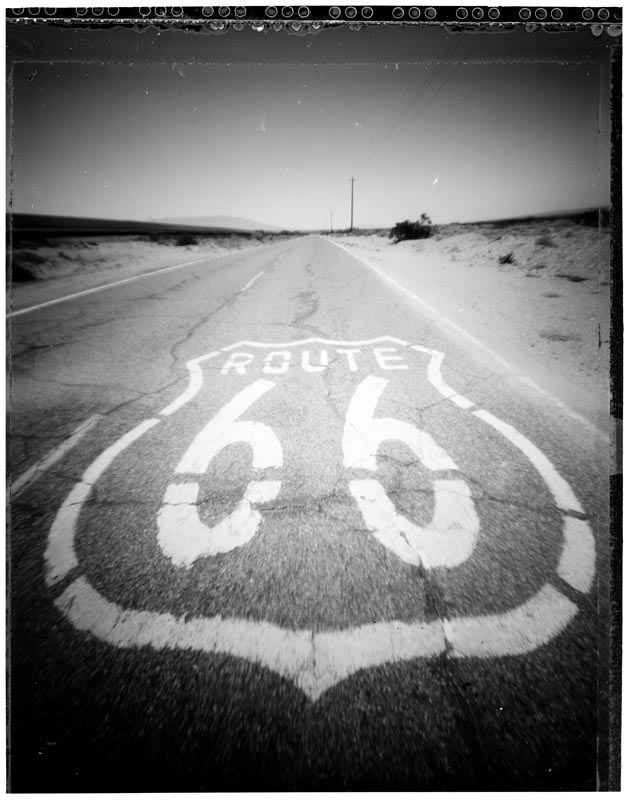

The Open Road

In the summer of 2006, the year of its eightieth anniversary, Julia and I flew to Chicago to drive the length of old Route 66 from its starting point at Michigan Avenue to its end at the Pacific Ocean in Los Angeles. Our  article on the history of the route, and on westward travel in the U.S. in general, was published in the Winter 2007 issue of DoubleTake/Points of Entry magazine. This is its conclusion:

article on the history of the route, and on westward travel in the U.S. in general, was published in the Winter 2007 issue of DoubleTake/Points of Entry magazine. This is its conclusion:

There will be the mesa you round, and the moment you stop and get out of the car to feel the silence, hear the stillness, listen to no wind blow through you. A deer will fright on a low crag across the road, start and stop, bound to the cliff top and lift its ears, run as the earth rumble grows. From out of the pass, the train will come, long and steady, brown cars, red cars, yellow, reminding you, as you stand and watch, that while you are always alone, you are always connected.

And then, finally – at last, you may think – curving and cornering through the mountain switchbacks on the stretch between Kingman and Oatman, Arizona, the old gold mining and western town where burros roam and Clark Gable and Carole Lombard spent their honeymoon night – you catch sight of the wide, sweeping valley below, and still more mountains beyond, and you wonder, as they must have back in ‘26, and on how many horses and wagons before: Does it never end? Does it go on forever, this country? Is there always another valley, another mountain, another plain? They say there is an ocean.

But you will arrive. And the road will return you to yourself, whether it is the route called 66 or another. Because Route 66, as Kerouac knew, as the makers of the TV series knew, is just the emblem of the open road, which is to say its essence. We are alone and connected, and the road tells us both.

In a world in which the daily coffee Americans buy may or may not enable a Guatemalan farmer to live, or the sport shoes we wear lead a Chinese child to labor 12 hours a day in a sweatshop; in a world in which the toot we put up our nose loses a child’s policeman-father his head in Rosarito, and the computer we buy starts a new life for a young woman in Bangalore (and the gasoline we put in our tanks fuels the terror against us) – in such a world of six billion people, to insist we can live by the libertarian ideals of an 18th century agrarian society of just under four million may seem a stretch of the common in sense.

And yet… And yet…

And yet, there are those who recoil to think they are born into an ant colony of genetically and socially contracted roles and regulations, that they evacuate the womb to be captured by government forms, numbers, and imprints before they are even really people. (Though the number that gets you cash from the Bank of America drive-in machine when you’re running low in Tulsa comes in pretty handy.)

On the road, at least – if not, soon, in Britain, at least still here – you can regain your anonymity, disappear into the human grove of earth at this overpass or that T, or along the “let’s see where that goes.” You can leave behind for awhile the Middle East, and Darfur, and Tamil Tigers, and the forgotten prisons of Myanmar – the my God, your God, whose God, no God – and try to remember something. Maybe you recall it in the Petrified Forest or great Meteor Crater of Arizona, maybe in the desert, maybe in a bar.

It’s like Buzz used to say over the credits each week, as he and Tod would first set out all over again in their Corvette: “Goodbye Pittsburgh. Hello world.”

There may be troubles behind and uncertainty ahead. But there is possibility too. And while your destination lies before you, for now there is the journey. Winds come up, and they cease. Islands of white cloud hang suspended in the blue. Fields go by. Towns go by. Rivers and bridges. Mountain. Valley. Mesa. Butte. In what seems a dream of life, and not life, which is to say life at last, and not a dream, the rhythm of the road, the quick of perception, both lull you and drive you on. You are individual and alive, and everything that passes catches the sun.

And so we begin.

by AJA

Banning, California; November 2008

Yay! Congratulations. Here’s to many more.

Naomi